The challenge for institutional philanthropy and the Occupy Wall Street movement may come down to the internal contradiction of the nonprofit sector’s financing structure. On the Occupy Philanthropy webpage, the list of upcoming events includes a panel, “Occupying Philanthropy: Increasing Foundation Support to Social Justice,” to be held at the annual conference of the Left Forum in March, the theme of which is “Occupy the System: Confronting Global Capitalism.” Meanwhile, the annual conference of the Council on Foundations will be held in late April and early May. It would be hard to imagine two more contrasting programs—the Left Forum’s agenda of anti-capitalist, socialist, and anarchist discussions, and the Council on Foundation’s gathering of well-heeled liberal and conservative philanthropists, whose institutions prosper on investments made in the corporate sector that Occupy Wall Street, here referred to as the Occupy movement, decries.

Can institutional philanthropy—foundations established by the very wealthy and capitalized by investments in the stock market, hedge funds, and offshore investments—support a movement that challenges the very capitalist economic system that sustains it?

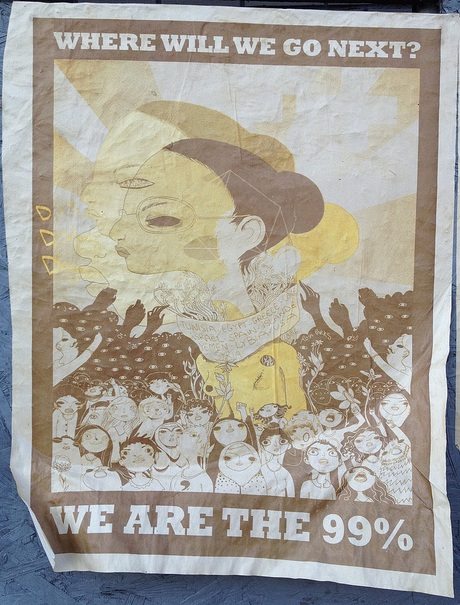

As of March 1, 2012, 62 people, largely from progressive funding organizations and foundations, have signed a letter on behalf of the nascent Occupy Philanthropy movement calling on institutional funders to provide financial support to the Occupy movement. The letter stated, in part, “We in the philanthropic community cannot let this moment pass. We have for so long wanted this kind of mass mobilization for justice. We have held conferences, gatherings, phone meetings, and spent countless sums in an effort to support the creation of a movement that is broad based in scope and calling for systemic change. Occupy presents a unique opportunity for the philanthropic community to creatively respond to these efforts and to the long standing and prior work of community organizations and leaders to promote economic equality for the 99%.” The letter’s signees include some respected private foundations long associated with social justice funding, including the Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation in New York City, the Quixote Foundation in Seattle, and the Rasmussen Foundation of Alaska. Progressive public foundations that raise money to make grants also signed the letter, such as the Funding Exchange and the Third Wave Foundation. And some philanthropic luminaries, notably Jerry Greenfield of Ben and Jerry’s ice cream, also signed.

However, the cumulative resources of the signers, largely from small foundations, don’t add up to much compared to the somewhere close to a trillion dollars of tax exempt assets in foundation endowments. The trustees and executives of the large foundations in control of those assets look a lot more like the boards of Fortune 500 corporations in terms of their social and economic status than they do the protesters who once resided in New York City’s Zuccotti Park or Washington, D.C.’s McPherson Park.

Still, institutional philanthropy has long had a streak of funders oriented toward repairing some of the damage that its business mogul financiers caused. In her 2003 book, Foundations and Public Policy: The Mask of Pluralism, Keene State College Professor Joan Roelofs argued that foundations may be impediments to social change and that their role is often to tamp down or soften the advocacy and organizing efforts of their grant recipients. That is, relatively strident activists become nicer, more mainstream, and less controversial with the assuaging presence of foundation grant dollars—and they almost always resist biting the hands that feed them and sometimes even avoid biting the hands that created the capital that feeds the foundations.

How do foundations interested in nonprofit due diligence fund a movement that operates significantly outside of a traditional nonprofit, 501(c)(3) structure, without even clear leadership delineations, decision-making dynamics, and governing boards? In other words, who are they funding? For a foundation sector increasingly focused on metrics, what metrics would foundation funders use for a movement that eschews a formal structure of demands and operates more nimbly? Indeed, Occupy often responds to events (for instance, Occupy protesters plan to remobilize in the spring for the May G-8 summit in Chicago), focuses on short-term actions (such as Occupy Salt Lake’s plan for protest theater about corporate influence at the Utah state legislature), or organizes to rectify specific injustices (such as Occupy D.C.’s Freddie Mac protests over the lender’s foreclosure on a Bowie, Md. homeowner).

Nonetheless, while acknowledging the constraints involved, there is no reason why institutional philanthropy cannot fund the Occupy movement, but doing so will require its leaders to consider several key questions, some of which follow.

Can Foundations Fund a Social Movement?

Of course they can. Think of foundations, such as Rockefeller Brothers, New World, and Field, that provided support to the civil rights movement, particularly to voter registration and voter protection efforts in the deep South. The progressive foundations of the young inheritors of wealth in the 1970s and 1980s—for instance, members of the Funding Exchange such as Liberty Hill in Los Angeles, Crossroads in Chicago, Bread and Roses in Philadelphia, and Haymarket in Boston—cut their philanthropic teeth in funding grassroots protest efforts, including anti-war organizing in the Vietnam War era. Now, the national head of the Funding Exchange, Barbara Heisler, is one of the Occupy Philanthropy signatories.

Like those earlier movements, the limitation is that there is no one “Occupy” to fund that then reaches every local manifestation of the Occupy impulse. To the extent that they can find reliable entities to handle the funds, foundations will end up funding only pieces of the Occupy movement—unless foundations themselves take on roles as fiscal agents or otherwise exercise some form of domestic grantmaking “expenditure responsibility.”

What Will Foundations Potentially Fund?

The Quixote Foundation has posted a number of suggestions about Occupy funding for foundations on their website, two of them in the grantmaking arena:

- Support organizations that help the Occupy movement. The National Lawyers Guild links demonstrators with free emergency legal help. Ruckus Society provides training…

- Support those who make the movement visible when big media looks the other way. Mother Jones covers Occupy demonstrations and gives practical information for engaging through events like Bank Transfer Day…Media Democracy Fund contributes money, strategy, and connection for the work these groups do.

In a way, this is similar to the funding strategy that has supported and built the Tea Party movement. The Tea Partiers don’t have much in the way of formal structure for funders to bank on, so funders have supported the national infrastructure of groups such as FreedomWorks, which gives voice and structure to the Tea Party’s amorphous cacophony.

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

Another funding-oriented website in support of the Occupy movement is the I Heart Occupy Campaign. One of the two contact names listed on the site is Tracy Gary, one of the several Pillsbury heiresses, who is well known as a philanthropic advisor for progressive funding programs and the co-founder of Changemakers, a public foundation to support community-based social change philanthropy. i Heart suggests several categories of funding for donors:

- Local General Assemblies

- Local to Global Communications

- Occupy Systems Resilient Technology

- Occupy Awareness Benefit (Fundraising) Conferences

- Occupy Audit and Financial Transparency

- Occupy Education

- Occupy Training & Skill Building

- Occupy Art & Benefit Concerts

- Innovation & Resilient Economies

- Occupy Politics

These could be categories of specific projects and also regional and national support structures for the movement. i Heart has created specific funding pools for donors around each of these categories, but notes that donations to Occupy Politics would not be tax deductible. But here is the danger. When one looks at some of the signatories to the Occupy Philanthropy letter and examines the information on the i Heart Occupy website, one is left with the feeling of looking into an insider’s club. Does the language of social justice, meaningful to the participants, rub others the wrong way, as if coming from a “holier than thou” pedestal?

How Could Foundation Support Harm the Occupy Movement?

One of the signatories to the Occupy Philanthropy letter, Harriet Barlow of the HKH Foundation, wrote a piece for Alternet trying to help institutional funders avoid the movement-stultifying effect of foundation support. Concerned about government restrictions on nonprofits’ engagement in partisan political activities, Barlow asks, “Why would anyone want to harness Occupy with the oversight of the Internal Revenue Service by putting it into an official non-profit organization? Put another way, if we believe in the value and power of this work (and, one might add, all genuinely radical political work), we have to find a way to pay for it that looks more like union dues than something a financial adviser would approve.”

Barlow is also concerned that a nonprofit structure for the Occupy movement will take Occupiers out of their encampments and off of the streets where they have been most effective. Agreeing with Quixote, she calls for funding Occupy’s emerging supportive infrastructure: “We need and have vibrant progressive institutions. In fact, many of them enabled Occupy to prosper. Supporting the existing infrastructure that allows interruption to be meaningful is crucial to the future of whatever comes next. Have you who cheer on the occupations sent contributions to the National Lawyers Guild which was everywhere defending the legal rights of all the occupiers? Or have you joined the Working Families Party or CodePink… or any organization that rolled up its sleeves for Occupy? Are you paying your dues to maintain a vibrant, independent media? These are all part of the institutionalized left that we should support.”

And Barlow also warns funders not to “drown” Occupy in money. “As far as we know, no one was paid to occupy,” she argues. “But occupy they did. And did…Throughout the fall, the OWS folks across the country did maintain the very good sense to reject the idea of paying themselves… But the fruits of that good sense will be erased with the prospect of salaries and

budgets to ‘institutionalize’ OWS… Give the determined old- or newcomers, ‘no strings attached’ moving around dollars, but not titles or commitments to do anything but pursue high-stakes action in solidarity.”

That is a difficult message for nonprofit leaders who wake up every morning and ask, “What have I done to raise money to keep my organization alive, to pay my staff, and to fund programs and services?” The model Barlow has in mind would fund Occupy much like labor unions—with members’ dues or other resources—and would mostly grants from large philanthropic organizations out of the picture.

Beyond Grants, What Could Foundations Do to Help Occupy?

More than half of foundation assets are invested in equities, the stocks issued by corporations and sold on Wall Street. Normally, foundations invest for maximum returns in order to maintain their floor for their five percent mandatory charitable distributions. In other words, foundations invest and maintain hundreds of billions of dollars in some of the corporations most strongly decried by the anti-corporate Occupiers. What could foundations do?

First, instead of focusing on their five percent mandatory payout, they could focus on how they mobilize and leverage their 95 percent in investment capital. Some foundations are now pursuing shareholder actions to change the behaviors of corporations regarding executive compensation or other issues. There’s nothing wrong with that, but an even stronger stance from foundations in sympathy with the Occupy movement would be to divest from those corporations which are the worst purveyors of the corporate excesses most challenged by the protestors. Foundations could follow a divestment strategy similar to the one that worked so well decades ago in South Africa.

Also, foundations could shift their investments into Market Related Investments (MRIs), investments that support the foundation’s mission rather than investments made simply for a maximum possible return. Investments in triple bottom line corporations and community projects are a laudable alternative to willy-nilly Wall Street investments.

Lastly, foundations could get off their assets and start paying out more and spending down by putting their money into nonprofits for social change. Quixote leads the way with a plan to have spent out entirely by 2017. By breaking through the five percent ceiling and raising payouts substantially, foundations can chip away at their institutional support for corporations and provide needed resources to the social sector. We will soon see if the funders of the Occupy infrastructure develop the heft and generosity that the conservative funders have shown to the Tea Party’s national networks—and if philanthropic efforts to aid Occupy can be built not just by self-identified activists on the left, but by funders who know that today’s political and economic inequities make for an uncertain and unsustainable future.